After Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, neighboring countries experienced an influx of refugees. Petry Groza S’12 and William Shaw ’04, S’08 are two Bethel alumni who’ve been able to offer direct support to Ukrainians who’ve fled, providing food, shelter, resources, and hope for new beginnings.

By Cherie Suonvieri

Led by Bethel alumnus, Petry Groza, the Regen Foundation has been providing direct support to Ukrainian refugees arriving in Romania, some who are pictured here alongside organization staff.

(St Paul, MN) — April 04, 2022 — Since the war in Ukraine began, more than three million people have fled the country, leaving behind their homes, communities, jobs—and, for many, family members as well. Russia’s attacks have left destruction across Ukraine, and according to the United Nations, more than 1,000 civilians have died.

As refugees pour into surrounding countries, neighbors have largely responded with empathy, opening their homes and offering what resources they have. We connected with two Bethel alumni, Petry Groza S’12 and William Shaw ’04, S’08, who’ve been organizing their respective communities in Romania and Poland to meet the great needs of those fleeing the war in Ukraine.

Welcoming Ukrainian Refugees in Romania

Petry Groza is an alumnus of Bethel Seminary’s transformational leadership program and serves as president and general director of the Regen Foundation in Fagaras, Romania. Situated on the southern border of Ukraine, Romania has seen more than 500,000 refugees enter the country in the past weeks, according to BBC—and Groza and the Regen Foundation have been quick to respond.

The organization has been providing temporary housing for Ukrainian refugees at its Horizon of Hope Center, a transitional home for young men, which was vacant due to the pandemic when Russia invaded Ukraine. The center has 26 beds, which have remained at capacity as families come and go.

“Each one of them has their own stories—and I listen to all of them.” — Petry Groza

Groza and his wife, Kyle, have been deeply involved in the operations and are working to help meet the needs of each refugee with whom they come into contact. They provide shelter and food, and they’ve taken people shopping for other necessities based on individual needs. Groza has also acted as a dispatcher at times, directing incoming refugees to the best border crossing, helping people find places to stay after they leave the Horizon of Hope Center, and rallying more community support.

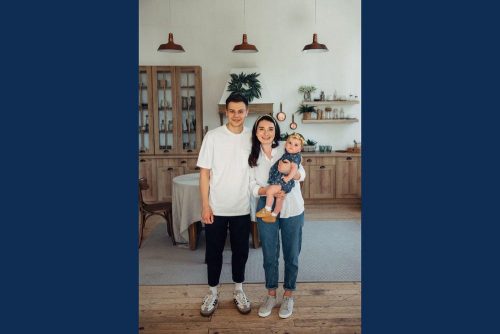

Petry and Kyle Groza (center) with a Ukrainian family that passed through the Horizon of Hope Center.

Many different people have passed through the Horizon of Hope Center—doctors, nonprofit workers, educators, artists. “Each one of them has their own stories—and I listen to all of them,” Groza says.

Like the young mother and father who worked as ballet dancers for an opera house in Odessa, Ukraine. They had just purchased their first apartment and moved in with their 4-year-old son and two cats. Two days later, the war began and they fled, leaving nearly everything they owned behind. They were the first family to arrive at the Horizon of Hope Center. Since then, Groza and his team have helped them arrange more permanent housing in Romania. “They had to start new. Leave everything behind,” Groza says. “I can’t even imagine myself in that situation.”

Then there’s the pastor who came to Horizon of Hope Center from Kyiv with his wife, three children, and his wife’s parents. They’d woken at 5 a.m. one morning to the sound of bombs, so they packed their car, left their home, and spent three days traveling to the border.

And there’s the woman who walked to Romania from Ukraine with nothing but a small bag and her 3-year-old child. She’d been dropped off at the border by her husband who was unable to leave the country, as most Ukrainian men ages 18 to 60 have been banned from doing, in anticipation that they may be called to fight. “The reality of war is very painful. I’ve never really imagined how painful it can be,” Groza reflects. “We’ve seen families that are separated and have lost everything. They are away from the language, places, and communities that they know.”

Petry Groza says it is through God’s provision that the Horizon of Hope Center has been able to welcome so many refugees to Romania.

Groza says he never anticipated that God was preparing him to serve in this way. When Russia began to threaten Ukraine, Groza says he, along with other Romanians, suspected that something was coming—but conversations about refugees didn’t start until after the war began. Romania reacted quickly, however, as government agencies, churches, and nonprofits organized in order to respond.

“I realize that God actually prepared our center for this. It was empty through His providence,” Groza says. “My heart is to help people. To share the gospel with them and just show them God’s love. That’s our vision. That’s why we are here in Romania. That’s our calling, to invest in these people who need regeneration right now. They need something new—a new place, a new start, a new beginning.”

Those interested in supporting the efforts of Groza’s team can donate through the Regen Foundation website.

Welcoming Ukrainian Refugees in Poland

Upon Russia’s invasion on February 24, William Shaw and his wife, Marta, were contacted by a missionary friend in Ukraine who had 60 families that needed places to stay. The Shaws opened their home to one of the families—a young couple, their 2-year-old daughter, and the child’s grandmother—but they knew they could do more.

The Shaws called friends, family, whoever they could think of to try and find additional placements for Ukrainian families. Then, they tapped into the network of people they work with to host an annual art festival. “We used that pre-existing network, our volunteers, and our resources to switch gears and focus on helping refugees,” Shaw explains.

William Shaw (center) with a group from his network, who’ve been working to organize spaces and resources for incoming refugees.

Their team has been on the phones and on the ground connecting refugees with host families and meeting needs in whatever way they can. They’re also planning to quickly renovate empty apartments and outfit them to support more families. “Here in Krakow, it’s filling up. People are sleeping in train stations. The stadiums are full,” Shaw says. “We want to try and create as much housing as possible, but we also want to take care of the people we house. We’re helping people connect to the doctor, find work, find schools. We want to offer them support that will help sustain them long term.”

The first family the Shaws hosted arrived quickly, on the day the war began. The family’s home is in Kyiv, but they were visiting friends in Lviv, a city in western Ukraine. With their bags already packed, they left for Poland as soon as the bombing began. “It was very lucky for Anton, the father, because he was one of the few fighting-aged men that made it out before the policy went into place,” Shaw says.

Anton, Nina, and their two-year-old daughter. After arriving at the Shaw’s home on February 24, they also worked to help other family and friends cross the border. They have since found more permanent housing.

The Shaws have a number of friends from Ukraine, and one of the families they know had to split at the border, the mother and three children able to cross and the father required to stay behind. The father is now working to bring aid to cities like Kharkiv and Kyiv. “That’s really hard for his family. It’s hard for him. And it’s hard for us, too.”

The family friends of the Shaws stood in line at the border for 24 hours, and some Ukrainians have waited much longer. In addition to finding housing, Shaw’s team has been providing direct aid to those waiting at the border as well, delivering supplies as refugees wait to register.

“This is going to be a long-term thing. We keep telling ourselves that this is a marathon, not a sprint.” — William Shaw

Shaw says that the need created by the war in Ukraine is great. Not only are there the individual needs of the Ukrainians entering the country, but systems are being taxed as well. Cellular networks in Krakow have slowed significantly. Parking has become an issue as more people enter the country. But Shaw and his team are focusing on the needs they are able to address.

“This is going to be a long-term thing. We keep telling ourselves that this is a marathon, not a sprint,” Shaw says. “A lot of people want to give right now, but once the news cycle changes, people start to forget. We’re going to need help, support, and finances for the long term.”

For those interested in supporting the work Shaw’s team is doing, donations can be made by visiting the SLOT Hospitality Network website. Shaw also recommended Josiah Venture, a missions organization he has worked with that’s sending buses of aid into Ukraine and bringing refugees back.

When asked why he and his wife have responded to the Ukrainian refugee crisis in the way that they have, Shaw says it all comes down to their faith: “We want to live with an open house and open hands. Scripture says whatever we do to the least of these, we do to God. We’re called to feed the hungry—to care for the other—and that’s how we want to live.”

Source: Bethel University – republished with permission